At fourteen, Aminata was hungrily looking in at the rice and sauce being served at her school in Freetown, Sierra Leone. By sixteen, she is married and pregnant. “My parents couldn’t afford to give me any money for food, so I dropped out of school and got into an early marriage to an older man.” As we Skype in a classroom, I in a spacious well equipped one in London and Aminata in a small, basic one, provided by the Global Giving charity in Sierra Leone, she and some of her classmates explain some of the problems they face. “My parents could not afford to pay my fees on time, I did not have a good uniform, I did not have any books and so I quit”, says Awobongowa, a shy sixteen-year- old from Northern Sierra Leone. She is now, like all the others in the room, married and pregnant.

Lunch fees are a huge problem for the girls of Sierra Leone. The steep price of meals ranging from 1000 – 4000 Leones means that many are left starving and those with poor parents go to school without any lunch. “I couldn’t concentrate,” says Aminata. With lunch expenses and school fees playing heavily on her parent’s minds, she was forced to leave. Older men came for her hand and she is now married to a man three times her age. Life now consists of cooking, cleaning and looking after her husband. “My life would have been better if I had completed my education,” she says.

Half a century after the country’s independence little has been done for the education of their children. Although all children face hardships the problems girls face are far more significant. “I really enjoyed school, but after my aunt died there was no one to pay my fees so I had to get married to support myself and now I have child” says Isata. Ironically early marriages increase poverty. “When a poor girl gives birth to a child, that child will be the poorest of the poor,” explains Miriam Mason-Sesay, the country director of EducAid.

Youth literacy rate for girls is only 37% with almost two thirds of Sierra Leone’s female population still unable to read. The illiteracy rate is especially high within rural areas. Yet for the hard working Sierra Leonean parents short of money, at the mercy of fee-hungry head teachers, it is simply not economical to send a girl to school. One of the girls, Hannah, talks of how her parents sacrificed her education for her brothers and how she now stays home to do the chores.

Fees are only a small part of the wider problem. Rocco Falconer, founder of Planting Promise, an organization that creates schools for children in Sierra Leone, argues the problem is also one of respect. “Girls aren’t respected,” he says, “a girl is not an heir to the family and is not the hope of the future.” Girls drop out of school on a daily basis due to conservative patriarchal customs which expect them to complete menial household chores even if it means putting their education last. Long lived traditions of early gift marriages, family management and female genital mutilation (FGM) are generally accepted as the status quo; FGM affect a high percentage of the female population and contributing to high infant mortality.

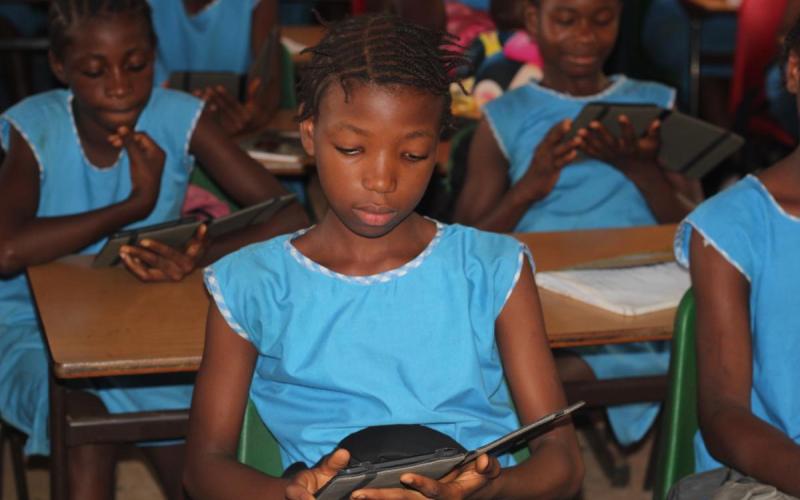

The problem, he goes on to say, is that there are no female role models: “Girls will only aspire for change if they are inspired.” The need to radicalize women and increase their self-esteem is something that is evident within all education projects. Girls who do make it into the education system face their own share of problems due to the quality of schooling. Resources are scarce; classrooms are overcrowded and hot, making it difficult for children to get an education. Over 40% of teachers are unqualified, with some being unable to complete the tests they set for the children or choosing not to teach to earn more money in tutoring. The concept of rote learning, where teachers simply copy out the textbook for children to copy is widespread and the lack of analytical thought prevents gender empowerment.

In addition to the quality of education many girls suffer from sexual harassment at the hands of the teachers they trust. Joshua, the translator, tells me how many girls, including the ones in the room, have suffered as a result of this. “Girls are very vulnerable to sexual abuse. Teachers will sleep with girls so that they don’t have to pay their fees. Sometimes with their parents’ knowledge.” By the age of eighteen over half of girls have experienced some form of sexual abuse.

Gender equality and empowerment remains one of the key Millennium Development Goals and are a prerequisite for poverty reduction and development according tithe 2011 UNIFEM-UNDP report. Girls under fifteen are five times more likely to die from childbirth. 40% will suffer permanent internal damage. Educating girls allows them to marry later and to have healthier children. Children will be more likely to survive and will have access to better education and women will be able to play a more active role in political and economic decision making. Empowering women is crucial as it has a direct impact on the family and subsequently the nation.

Programmes are in place to create change in Sierra Leone. The Global Giving campaign ‘Educate A Girl, Educate A Nation’ works exactly for this. But the lack of funding for projects such as this mean that change is not yet on the cards for these girls. The future of Sierra Leone needs education, liberal development can only come from social change. As I finished talking to the girls I asked Joshua if I could call one of the students later on. He chuckled grimly. “If they could pay for a phone, they could pay for their own education.”

By Iram Sarwar